Jeffrey Luke’s Brazilian Diary

October

15, 1999

From Seattle, Washington

"Resist the Temptation to Buy Expensive Luggage"

--from Life's Little Instruction Book

by H.J. Brown, Rutledge Hill Press, 1991

So why did I just dump $620 on a single black suitcase? Because it's made out of black ballistic Cordura Bomb Cloth, according to the tag that was attached to its handle at the luggage store, "The most durable luggage fabric made."

Now that I have made the big purchase, I'm wondering why I bought such an expensive suitcase. I'm a photojournalist, and the pay isn't so great. This suitcase cost me a month's rent. What is Bomb Cloth going to protect me from anyway? Will it save my clothing from a bomb that a terrorist places in my plane's cargo hold? Perhaps this type of bag is used by terrorists to transport their own incendiary devices. I never asked the salesman why.

I bought this piece of luggage because I just received an invitation from Dr. Randas Batista, one of the finest heart surgeons in the world, to visit him in Brazil. I had the opportunity to photograph him at work when he came to the United States to teach cardiac surgeons here how to perform the technique that he has developed. His procedure is so stunning in its simplicity that cardiac surgeons, who often prefer verbose descriptions of everything, have decided to pass on calling the technique "Left Ventricular Reduction Surgery," and instead just call it "The Batista Procedure."

The procedure has already saved many lives around the world. The surgeon cuts a piece of living heart muscle out of the wall of an enlarged heart in patients with congestive heart failure. Then he sutures the heart back together, and the smaller heart functions more efficiently.

Like its name, the procedure is very simple. It has to be, because Dr. Batista works under very primitive conditions at his rural hospital in a poor region of southern Brazil. He has neither the equipment nor money that North American doctors enjoy, so he has learned to work with only a few operating instruments. "Some doctors come to my operating room, they see my equipment, and they say it looks like a dentist works here," Batista says.

Dr. Batista tries to solve his patient's problems in whatever way he can. "Your president from the United States, Teddy Roosevelt, said, 'You have to do what you can, where you are with what you have.' I live by that here in my hospital."

Dr. Batista recalls that I photographed him in the operating room this past spring. He sent me an email the other day. Like the surgeon, the note was kind, simple and functional.

"Hi Jeff. Wellcome to the jungle on October, Randas."

I have decided to go to Brazil. This is going to be an event like no other in may life. I can feel the winds of change. So I need a suitcase that can endure whatever Brazil throws my way. I don't know whether I'll wind up traveling through the thick of an Amazon Rainforest or fighting my way through the streets of Rio de Janeiro, cameras and clothing in tow. The only thing I know at this moment is that in one month I will be in Brazil.

So yes, $620 still seems like a lot of money. But when I look at this black ballistic Bomb Cloth case with its double reinforced zippers, special compartment which holds two suits, reinforced steel handle and rollerblade wheels which can handle a 200 pound load at 35 MPH, I think about James Bond. I don't recall him ever asking how much it would cost for the new turbocharged jet rocket car with bulletproof glass and gun turrets.

If 007 were going into the jungles

of Brazil, he'd bring the best.

Jeffrey Luke's Brazilian Diary

October

22, 1999: 9:10 pm.

From Curitiba, Brazil

My plane touched down in Curitiba at 1:34 this afternoon. Dr. Batista said he'd be there at the airport to pick me up, and he was. So there I was, pretty amazed that a world famous cardiac surgeon was there to meet me. The first thing he did at the airport after we'd said hello was buy some candy-covered peanuts from a woman at a little stand. From the way he got along with her, you could tell he'd been there before.

He drove us in his silver pick-up to a lunch spot. As he drove we munched on the peanuts. They were scrumptious, and came packaged in a paper cone, the type that's used to serve water at those coolers in office buildings, only bigger.

We arrived at a wide-open cafe. It had long, clean white tables and a bunch of different kinds of foods in a buffet arrangement. I went for the rice, beans, eggplant, and vinagrete, a Brazilian salad. Dr. Batista ordered his meal from a man who walked through the aisles with skewers speared through different kinds of meats. He chose some beef, a big chunk of steak with a bunch of fat attached, and was offered some pheasant, which he accepted. The waiter pushed the cooked bird off the skewer, and when he had walked out of earshot, Dr. Batista told me it was a joke. "It's really chicken," he said, "but the waiter offers pheasant as a joke. It's a kind of humor that you learn if you're here long enough. You see, pheasant costs 100 times as much as chicken in this country, and you'd never be able to buy it here. So it's a way that they kid around with you. If you were in New York and a waiter offered you pheasant and served you chicken, you could sue the restaurant. But this is Brazil. Things are much different here."

If you ever have the chance to have lunch or dinner with a cardiac surgeon, you must try it. There's a beauty to the way they cut their steak. I'd have to say it's in the precision of their cuts. They use the same hands and the same coordination for making incisions into the human heart. So even though their making cuts into a dead animal, there is care and technique devoted to even the most simple cuts.

As we ate, he told me that he'd recently been in São Paulo to perform the operation that has earned him a great amount of attention from those who think he's a genius as well as those who think he's crazy. "I'm pissed at the surgeons in São Paulo right now because they don't want to let me operate on a patient there who needs the surgery," he said. "They are afraid that if I operate and he dies, they will look bad, because they will have a surgical fatality on their hands.

"So instead they will let him stay in the ICU (intensive care unit) and die there. That way he will not be a surgical fatality, he will just die. They are afraid to look bad, but I don't care what people think of me. If I operate and the patient survives, his life will be better, he will be able to go out and do things on his own or with his family. But if he stays in the ICU he's going to die soon. I'd rather do the operation that he needs and not be concerned with what people think of me. I know the operation works."

We talked about why his surgery was met with such magnificent acceptance two years ago when word first caught on in the U.S. He was featured on ABC's 20/20 and PBS's NOVA, and a number of prominent cardiac surgeons in the U.S. expressed great enthusiasm for the procedure, which supplanted the need for heart transplant surgery for patients with enlarged hearts. Surgeons began to perform the procedure in great numbers, and about a year and a half later, they stopped.

I asked why his procedure became unpopular so suddenly, and he explained that hospitals were not making very much money on his technique. In some major medical centers, he explained, doctors were getting paid a much smaller amount to perform his operation than a heart transplant. One surgeon performed 300 of his operations and now no longer performs any. "Why did he stop after so many operations?" Dr. Batista asked. "Not because patients were doing poorly. If that were the case, he would have stopped after 10 cases. The top people in the hospital looked over the amount of money they'd made at the end of the year, and instead of making $20 million dollars, they'd made $19.9 million, and someone said, 'Look, we're doing this Batista surgery and we could be doing another that earns more.' So for them, it wasn't a case of losing money, it's just that they could have been making more."

He went on to explain that he believes that the operation will be better received in India and Asia, where people are poorer. India is so crowded, he said, that it's entire population of 1 billion would fit in the space occupied by California, Washington and Alaska. The entire population of the U.S. is only 250 million, a quarter of India's size. In India, he explained, people are so poor and so sick that almost anything you do will help them. In one week, that's just what he's going to do.

After lunch we drove to a petroleum company where negotiated a price for 5,000 liters of diesel that he needed for his farm. The petroleum saleswoman stuck to her price of .5025 reais (the Brazilian currency) per liter, and he insisted on .50 even. They went back and forth for a while, and he finally made the purchase. On the way out told me that in Brazil, there's an understanding that everything's negotiable. It's not like in the U.S., he said, where you can't question the price of things.

We ran a few errands together and then went to his farm. It's got wide open fields, rolling hills, a bunch of horses, stables and workers, all of whom wear cowboy hats, cool pants and boots, some adorned with spurs. I don't know exactly why it's called a farm, because I always associate cowboys and branded horses with a ranch, but when I think about it, it's probably just a regional word choice. The wild west in the U.S. is known for it's cowboys, campfires, gunfights and ranches. I don't associated ranches with Ohio or Iowa, I think of that as farmland. So although he calls it his "fazenda," which translates to farm, it's really a ranch.

I'd been off the plane from Seattle for less than 3 hours and I was galloping up a grassy hill on the back of a brown mare. Dr. Batista and the farm hand in charge of his horses took a ride through a few deep valleys because they need to build a tank to provide water for the grazing horses.

The more we rode, it became evident that horses

are a major part of Dr. Batista's life. He truly cares for them. Aside

from our talk at lunch, he never once brought up surgery. Out of respect,

I still call him Dr. Batista, but no one else seems to use that formality, and

without that title, you'd have no way of knowing that he was anything but a dedicated

rancher, a cowboy at heart. As we rode over one hill, he warned me to stay

well behind the stallion he was riding, "Because you are on a mare, and it is

spring time. If you get too close, he will jump and wind up on your shoulders."

We finally returned to his home after dark. Dr. Batista unfolded

a white napkin which he had used to wrap the bones from the steak he'd had for

lunch. He gave them to his two labs, Buck who is black and a yellow lab

whose name I haven't yet learned.

Dr. Batista's wife, Odessa, was waiting for us and served us fresh bread, cheese and tea. She was so kind, warm and gracious. The day came to a close with the three of us in the living room, all of us talking, Dr. Batista smoking a hearty Cuban Cigar.

I feel so fortunate, truly blessed to be in this country with these wonderful people. I have the sensation that those professional athletes describe after they've just won the World Series, or Wimbledon, or the Superbowl, when the reporter asks them, "How do you feel at this moment?" I've heard them say, "Amazing...but it hasn't really sunken in yet. I'm sure it will hit me later."

That's exactly where I am.

Jeffrey Luke's Brazilian Diary

October

23, 1999: 7:00 pm.

Curitiba, Brazil

My first full day in Brazil began with a great breakfast. Dr. Batista's wife, Odessa, had gone to the bakery and bought fresh bread which she served with butter, cream cheese and hot coffee. On the table was a box of corn flakes, which sat right next to my place at the table. The evening before, Odessa had asked me what I usually eat for breakfast in the U.S. I told her that cereal is a pretty regular thing, except for when there's more time for a treat like pancakes or French toast.

The thoughtful hostess that she is, Odessa got corn flakes just for me. It was so kind of her, and made me feel so welcome. I thanked her for her generosity and let her know that I want to share in the things that are typical here in Brazil. Odessa has done so many things to make me feel at home.

After breakfast, Dr. Batista showed me his laptop computer. It's a small, lightweight beauty of a machine. We gave a try at getting it to upload my first entry to the web, but ran into a few problems. After a short while, he said, "Let's go to the farm and work. There you will discover the solution to the problem."

That is the way he solves problems. He says the mind is like an iceberg, with the conscious part like the 5% above water, and the unconscious part the 95% below water. The unconscious part, he says, is much more powerful, and to get it to work, all the conscious part has to do is ask it a question. As we drove to the farm, he told me that if you have a problem, all you have to do is ask for the solution, and in time your mind, which is like a computer, will search for a solution. "If there is no solution," he said matter-of-factly, "then you don't have a problem."

Dr. Batista picked up a white plastic cup from his truck's cup holder, and said that if he asked the question, "are all cups white?," then his brain would think about it subconsciously. "When one day I come across a blue cup, my brain recognizes it and says, 'look, here is a blue cup.' Because you asked the question, the brain can find the answer. He says everyone's brain is like a computer, and he learned how to use his by asking questions.

As we continued to drive, he gave another example. "Say one day I asked my brain if there are any gold bricks in the street. If one day I see one, my mind will notice it, and alert me to it. But if I never ask the question, I will just pass that gold brick by, because I never asked my brain to search for one.

"Some people have said that I got lucky in discovering this heart operation, but they do not realize that this discovery was not a thing that I found one day," he said. "I have been dissecting hearts from animals since I was a kid, and studying them. It was only when I was older that I came across the hearts of the buffalo and the snake it had fallen on, and when I dissected their hearts I could see that although their sizes were different, they looked exactly the same. I could compare them to all of the hearts I had seen since I was younger. So the discovery I made of the importance of a normal ratio between the heart's mass and diameter is something that my mind had been working on for years."

We finally arrived at the ranch. Yesterday when we had been there and rode the horses across those vast grassy hills, I thought that he owned one or two of the horses, and was just borrowing them from the stable where they were kept. Today I learned that it is his stable. The ranch hands there work for him. His farm includes the the 40 or 50 horses in open fields, the cattle, sheep, tractors, as well as the fields of corn and alfalfa.

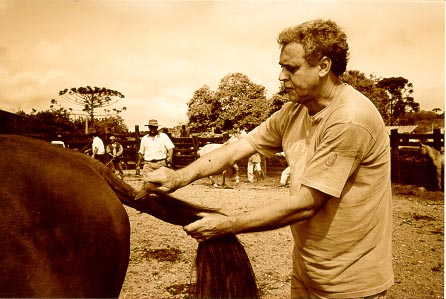

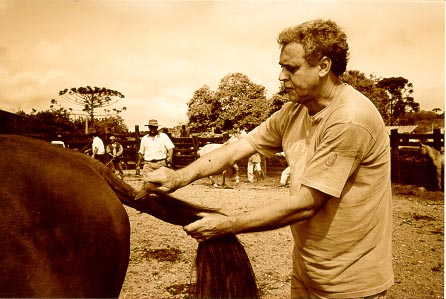

We spent the entire day cutting his horses' hair. First their manes, then the hair on their tails. These horses are a breed of wild mustang called Raca Crioula. They are indigenous to this area, and their hair is supposed to be cut in a certain way for breeding purposes. In prepartation for the spring mating season, we were horse hairdressers.

|

|

|  |

|

While taking a break to wait for a truck to arrive on the farm, I sat on the ground, and finding a round white rock the size of a quarter, I placed a smaller rock on top of it. Then I found an even smaller rock, and balanced it atop the other two. And in the midst of this playing, I figured out the simplist way to upload my Brazil Diary onto the internet.

I told him that I'd solved the problem while playing with stones. I think he was proud that his words of advice had worked. "You have to be relaxed after you ask your mind a question," he said. "That way, when your mind has found the answer, you can be receptive to it. You have to have the window open so you can get the answer. If you are busy with other things and thinking too much, your conscious mind will be closed and won't be able to receive the answer from the unconscious mind."

On the drive home from his ranch, we followed a long winding red clay road. I saw more cattle, land, and horses, and he pointed to a stand of towering trees, which he told me were eucalyptus. Later he pointed to persimmon trees. I asked him if we were still on his farm and he said yes. His farm is huge.

I am exhausted. I just showered and no longer smell like a horse. It's time to head over to his friends' house for dinner. I have not received my luggage from American Airlines. It did not arrive with me in Curitiba. I am officially out of clean clothes. Fortunately, I never let my camera, film or passport out of my hands, so the most crucial parts of my adventure are intact.

Just one note on luggage. No

matter how durable your suitcase, no matter how intelligently it has been constructed,

the airlines can lose it with the greatest of ease.

Jeffrey Luke's Brazilian Diary

October

24, 1999: 9:00pm

Curitiba, Brazil

Today we got on our horses and ran in the Cavalgada, a springtime ritual in which every cowboy and cowgirl and everyone who wants to be one goes for a long ride through the farmlands on the outskirts of Curitiba. Brothers, sisters, girlfriends, boyfriends, mothers and fathers ride through the dirt and clay backroads, everyone weaving through the countryside in a cloud of dust, the clopping of hooves, cracking of whips and laughter.

It was like a marathon, except with no start or finish line. There was no hurry to get anywhere, and to me, this seems to be typically Brazilian. While riding, I had people on my right and left, total strangers all dressed in their Sunday riding duds. And they smiled, and a few passed around a bottle of beer or cachaca, a Brazilian rum. A few dogs scurried around between horse hooves, trying to keep up with the procession without getting stepped on. Dogs love this kind of action.

I started the ride near Dr. Batista, but my horse really liked to run...they told me later that he was among the best performers in jumping competitions. So before long, I found myself at the front of the Calvalgada, and I had to struggle against my horse to try to get him to slow down. There are two things that I am very glad I brought to Brazil. One is the ability to ride horses, which I learned at the age of seven when my parents bought three horses and built a corral next to our house in North Truro, Cape Cod. I felt proud when I overheard Dr. Batista tell a friend, "Ele sabe andar," which means, "He knows how to ride."

The second thing I'm glad I brought here is a pair of boots that I got at REI in Seattle last week. They are the kind that Australians have worn since the 1800's on the outback, dark brown with two tabs on the top that allow you to pull them on easily. They also have an elastic mesh on the sides that gives your feet some flexibility and lets them breathe.

I had no idea I would be spending most of my days on a ranch when I was in Seattle, but since Dr. Batista had mentioned that he likes to go and work on his farm with tractors and horses, I figured that to be safe, I should bring a pair of boots that could trudge through dirt, rocks and pebbles and keep my feet dry and free from shards of stone. It turns out Dr. Batista wears the same boots.

The Cavalgada went on for hours until we arrived at this big lunch tent set up on a wide open green field. There was music, rice, beans, salad and bread, along with tons of beer and soda. To top it all off, there was a raffle. Dr. Batista is probably the best known man in the area. They know he's a surgeon, but today the buzz was about something else. He had donated a horse to the auction, and it was definitely the best prize. So the master of ceremonies jabbered incessantly about the "beautiful horse from Dr. Randas Batista's ranch that will be auctioned off soon."

Someone else had donated a buffalo, and because I was one of the riders, my name was automatically entered in the raffle. Among my new friends here are Dr. Batista's two sons who took part in the days' festivities, the question they asked jokingly was, "What will you do if you win the buffalo (or the horse)?" I hoped I wouldn't win, because, as I told them, it would be such a hassle trying to get a buffalo through customs at the airport. But at the same time, it would be absolutely terrific to be the American who has the Buffalo, the guy who won the raffle at Cavalgada, who was so proud of this animal that he was bringing it back to the United States. It would be my child, my pet, my baby. I would take care of it. Unfortunately, I did not win, which is probably best anyway. It would have been so cool. I think I'd be a good buffalo dad.

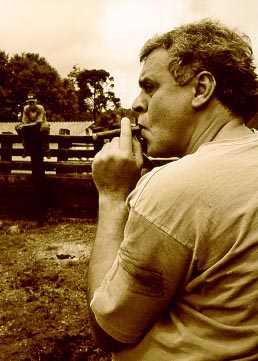

After we finished the Cavalgada, we returned to the ranch. Most of us were pretty tired from about six or seven hours on horseback, so we washed down the horses, fed and watered them, and sat down in one of the corrals. Dr. Batista lit up a cigar and his sons and the ranch hands and I talked about the ride, the horses, and how we needed to get some salt for the horses to lick.

One of the ranch hands gathered up a bunch of the hair that we had cut from the horses' manes and tails yesterday. He put the hair on the ground along with some dried sticks and leaves, in order to burn it all in a fire. Then someone picked up a dead rat that I had noticed a day earlier in the grass and carefully avoided. He placed it atop the pile of hair and sticks and leaves. Then someone else lit the whole pile with a match and before long the heap was flaming, crackling and smoking. Of all the things in the pile, I thought about the dead rat most. I have never seen an animal of any kind, living or dead, burned before me.

I always thought of cremation as a pretty sacred thing. But out here on the Brazilian outback, the afterlife of a rat was not anything to consider for very long. The ranch hand who placed it on the pile didn't say a thing, and smiled as mischieviously as an eight-year-old as he placed it on the pile to burn. I stood there looking at the burning heap, and when I could no longer distinguish between the rat, its tail, the burning branches of the Eucalyptus tree and the horse hair, I turned to a ranch worker and asked, "Where is the rat now," pointing quizzically to the sky, hoping that the soul had already left the body for rat heaven. The ranch hand pointed to the smoldering mess on the ground and said, "it's somewhere in there."

Jeffrey Luke's Brazilian Diary

October

25, 1999

Curitiba, Brazil

My luggage has still not arrived.

The worst thing that I have lost with my luggage is not clothing, it is a book that I made from the best photos that I took of him when he operated in Seattle. I even wrote a text in Brazilian Portuguese so that he could show it to his friends, family and other surgeons here in Brazil. I see the care and effort he puts into his horses, his family, and his surgery. I just want him to see what I put into my photos and writing for him. Along with the fact that I don't have his book, I've been wearing the same clothing since I arrived in Brazil last week. I only have three shirts to wear. One of them is a white tee shirt, and while I was weaaring it at the ranch a horse slobbered on it and then I got a bunch of dirt and grit on it and now I cannot wear it.

The second shirt is is a brown polo shirt. I am really glad to have packed it in my carry-on bag because I was invited to a dinner party the other night with Dr. Batista's graduating class from medical school. They dressed nicely, and I'm glad I had a decent shirt. Only thing is, after we ate dinner, everyone split up...the men went into a back room and the women stayed at the dinner table. And the men sat around a big table and smoked cigars. It was almost comical, that you could find so many people who liked cigars in one room. How could they coordinate it? It was like cigar peer pressure. So they smoked and drank beer and red wine and told stories. I listened. I had difficulty understanding their jokes, though I do understand Brazilian Portuguese pretty well. Jokes involve a lot of slangs, idioms, and swears, and none of those were one my language tapes in Seattle. The other thing that complicated things is that people who have lots to drink and speak a foreign language -- or any language -- are often difficult to understand.

One of the jokes had everyone at the cigar table splitting their sides in laughter. Except me, because I didn't get it. So I'm sort of smiling in an amused way as though I got the joke (I'd feel stupid looking serious when everyone else is falling out of their chairs and spilling beer on themselves in laughter)...and then someone looks my way and says, "Do you get it?" And at the moment I'm about to admit that I don't really understand, Dr. Batista jumps in on my behalf and tells him, "Oh, yeah, he understands Portuguese well."

I sat at that cigar table in my brown polo shirt until two o'clock in the morning, and it stinks so badly of cigars that although it looks fine, it's so unappetizing to slip into after my morning shower...My one remaining shirt is a blue and green polo shirt. I wonder if I can possibly wear the same shirt for an entire week. Yes, I could ask someone to wash my other shirts, but I just arrived here and I don't want to put anyone out. I could wash it by hand in the bathroom, but then what would I wear while it hung to dry?...So you see, everything gets complicated on the road.

If anything can be learned from all of this, it's probably to pack as much clothing as possible into your carry-on bag when you leave the country. You have to realize it may be the only bag you'll have when you arrive at your destination.

With all of the problems I've had because I have no clean clothes to wear, the worst part of it all is that I don't have any of the photographs that I took of Dr. Batista when he was in Seattle to give to him as a gift.

Yet

I think this might also be the best part. Because it shows that he is the

kind of guy who would bring me into his family, into his home, and expect nothing

in return. He has not seen any of my photography and never once asked to

see the photos I took of him operating in the U.S. He has been nothing but

kind, generous and accepting. This baggage debacle shows that he's willing

to share these good things in life having received nothing up front, and expecting

nothing in return. He is a good friend.

|  |

Jeffrey Luke's Brazil Diary

October

26, 1999: 8:59 pm

Curitiba, Brazil

Today we operated.

I don't know which is the coolest job in the world; to be a heart surgeon or to be the photographer of a heart surgeon.

The way these days unfold has a beauty to it. Dr. Batista and I are similar in three fundamental ways. Neither of us like to do too much planning, we both like to keep things simple, and we believe that you should have fun when you work; if you don't, you have the wrong job.

So last night, before we went to bed, Dr. Batista told me that we will operate today. I asked him what time we'd leave the house, and he said around 8:30 am. I woke up at 7:30 and took a shower and dressed in my brown (smoking) shirt and stretchy grey Banana Republic jeans (the best pants with which to be stranded in a foreign country, if you can only have one pair -- they're great for riding horses).

Odessa had already been awake and placed fresh bread, butter, cheese and hot coffee on the table. She told me to sit down and enjoy, so I did. It was about 8:10. I asked where Dr. Batista was, and she said still sleeping. After we'd finished eating, Dr. Batista woke up and sauntered into the living room wearing his operating clothes. He lit his cigar. I joined him and we talked. He likes to start his day at his own pace.

I do the same thing in Seattle. I give myself a good hour or so in the morning for waking up, taking tea and watching the sun come up, looking out the window at the blue sky. So we have shared the beginning of our days lately. I can't believe it sometimes, like at this very moment, that the most innovative heart surgeon on earth has invited me into his home, and that we begin each day together.

[I just have to add this note, because as you know I'm writing this at night, and I just heard the funniest thing. Dr. Batista is taking his nightly bath, and I heard him start to shout some unintelligible words, then he started laughing, and now he's singing in an operatic voice. I was so perplexed at what was happening in the bathtub that I asked his son, Joubert, what was going on. He told me that he dad was watching the novelas, which is short for telenovelas, which are the popular Brazilian soap operas. He has a little t.v. in the bathroom, and appartently he loves these shows. He's been talking to himself (and now Odessa, his wife) in a really dramatic voice.]

Back to this morning. He finished his cigar and we hopped in the pickup and drove to the hospital. At his office he talked a bit with his secretary (her name is Isabel, and her name is embroidered on her lab coat as secretary for Dr. Randas...so that is how I'll refer to him for the remainder of this entry). After stopping in his office briefly, I changed into operating scrubs, cap, shoe covers and face mask. You'll recall that he left home wearing his operating clothes. This is unheard of in the U.S., as surgeons never wear clothes from outside the hospital into the O.R. (operating room). But he doesn't have problems with infections as do surgeons in the U.S.

We walked into the O.R. together. He reminded me not to touch anything, and then let me do my thing. I've been photographing heart surgery for about a year, and have photographed a number of surgeries. In that time I have learned a few things that have been a great help in the O.R. I share these with you in the event that you one day decide to become a cardiac surgical photographer (I know it's a somewhat specialized discipline) or so you will simply have some inside information on what counts in the O.R.

The first thing you want to do is tie the top strap of the operating mask above your ears firmly, but let the bottom strap stay kind of loose. The reason for this is that if the bottom strap is also snug, whenever you breathe, if you wear glasses, you'll fog them with each breath. So you'll try not to breathe when you're hovering over the beating heart, bracing yourself as you take the photo. Dizzy is one thing you don't want to be when you're above the operating field. If you don't wear glasses, you're lucky because you won't have the fogging problem. However, you may get sprayed in the face with blood one day, and you'll wish you had glasses on. So consider safety goggles.

Always prepare yourself for any cuts the surgeon may make into the aorta, or, in Dr. Batista's case, into the left ventricle. Blood will spurt out and it is really unpleasant to have someone else's blood squirt your way. I've been very quick and have remained relatively dry. Just stay on your toes.

Try to eat a good meal before surgery, because you never know how long an operation will take. The first heart surgery I ever photographed lasted 8 hours. You don't want to go that long without eating. Surgeons do. I don't understand how they manage.

The famous war photographer, Robert Capa, once said, "If your photos aren't good enough, you're not close enough." This holds true in photographing heart surgery, but there is a very delicate balance to maintain. It is important to get close enough to the surgeon, his hands, the heart and the tools to get a powerful shot. But you don't want to get so close you're in anyone's way. It's one of the things you have to guage for yourself.

You really have to keep as alert as the surgeon during the operation to get compelling photos. The best photos often come unannounced, and if you're in the right spot, if you've chosen either color or black and white film -- whichever suits the photos best -- with a good exposure, and you've got sharp focus, then all you have to do is time it right. The whole thing becomes instinctual after a while, yet you always have to anticipate what might happen and imagine what would make an amazing shot.

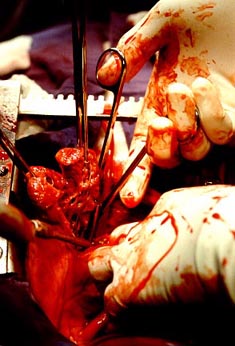

|  |  |

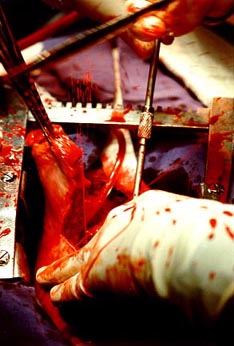

| This sequence of shots show Dr. Batista's hands as they excise a section of heart muscle in order to decrease the diameter and lower the wall tension in a patient's enlarged heart. In the last photo the spray of blood is visible after two coronary arteries have been severed. |

|  |

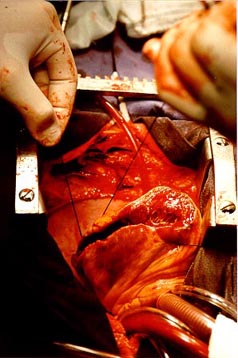

| Dr. Batista sutures the heart back together after removing a section of the left ventricle. |

|

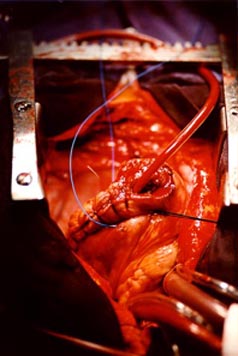

| The section of left ventricle moments after it was removed from the patient's heart. |

|

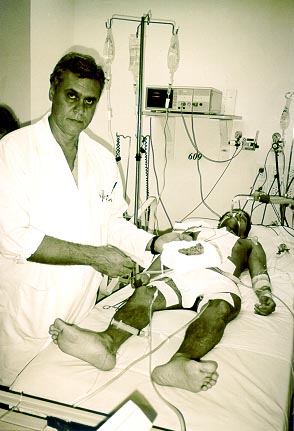

| Dr. Batista holds the chunk of heart tissue as he waits for the effects of the anaesthesia to wear off. |

Today's surgery went well. It was great to see Dr. Randas at work. He doesn't have the hi-tech facilities that North American surgeons possess, but he gets by just fine. I think that his sensitivity to the patient more than makes up for the lack of equipment. The patient today was a 40-year-old man with an enlarged heart. He was about 5'10" and 200 lbs. The cause of his enlarged heart is unknown, but it was a lot smaller once Dr. Randas snipped a large chunk out of the septum. It was amazing to see the piece of heart muscle contracting on its own once he had placed it in the stainless steel tray. I just looked at this piece of muscle, detached from the body, moving on its own. I thought how magnificent life is, and I took a photo. This is the first time I've been in an operating room where no one spoke English. It is otherworldly to hear the Portuguese flutter through the air during heart surgery.

After the surgery, the patient's parents approached Dr. Randas. They were so thankful to him for operating on their son. "Thank you, Dr. Randas, Thank God for you, Dr. Randas," his mother said. "Our son was so sick for so log. No one could help him."

Dr. Randas let them into the room where the patient had been delivered after surgery. He was still unconscious under an anaesthetic torpor. Dr. Randas told the parents (this is all happening in Portuguese) that as the patient comes out of anaesthesia, their sense of hearing is the first to return. He told them to talk to their son, that he may hear them. Whether he actually could or not seemed irrelevant. The beauty of the moment was in the mothers' walking up alongside the bed, and whispering how she loved her son, how he would do fine, how the operation was a success. It was a moment that I will savor, as it spoke of the way Dr. Randas helps his patients and their families in a sincere way.

After the parents had left, Dr. Randas could have left as well, placing the patient in the hands of the nurses and instructing them what to do in a number of scenarios while he is away in the afternoon and evening. He stayed with the patient. He spoke in his ear and told him that everything went well with his surgery ("Tudo foi bem com a sua cirurgia"). He felt for the patient's pulse, checked for edema in his ankles, measured the flow of the intravenous mediations. He spent time attending to all of the details of the patient's recovery. It was something I admired, for I have seen many different heart surgeries, yet never seen a surgeon follow through in such a thorough way.

I called the baggage people in São Paulo and they said that my suitcase had been delivered to the airport here in Curitiba, that I could pick it up. I told Dr. Randas that I was going to take a taxi to the airport. He told me to relax, he was going to drive me there. He did, and now I have clean clothes and a great book of photos to give him in the morning over hot coffee and fresh bread.

As I mentioned earlier in this entry, Dr. Randas had been in the bath. After his bath (which he enjoys with a guarana soda and a couple of mangoes) he came back here to the living room and had a cigar. We talked for a while. I asked what he found so funny about the telenovelas. He told me how they are very different from North American soap operas. Here, in Brazil, the best actors are in the novelas, and the worst go into films, whereas in the U.S. it's the other way around. The novelas are like mini-series in the U.S., only instead of running for three nights, they last for five or six months. The one he was watching tonight followed some Italians as they immigrated from Italy to Brazil. He said that Brazilian novelas are really popular around the world, and are on television in Mexico, Portugal, Spain and China, among other countries.

We talked about a bunch of other stuff. He called the hospital to make sure today's patient was recovering well. He left a phone number where he could be reached tonight if any problems arise. He started to get tired, and said he's off to bed. He said I could continue using his laptop computer. Not only am I here out of his kindness, but he opens the windows to the world via the internet with his computer.

To all of you who have been

reading this diary, I thank you. I keep you in mind as I mix with people

here, holding all of these ideas in my head to take home and share with you at

the end of the day. I am fortunate to be able to share this adventure with

you, and I wish you well.

e-mail

me: jeff@jeffreyluke.com

Jeffrey

Luke's Brazil Diary

October 27, 1999: 9:34pm.

Curitiba, Brazil

This morning as we shared "O Café da Mañha" (breakfast, though literally it means, coffee of the morning), Dr. Randas and I talked about how nature is very simple, and people complicate things. He said that the worst thing that ever happened to science was the Ph.D. He said when people start to think too much they make problems and confuse themselves. Then he said that if you are a simple person, you will see things in simple ways. If you are a complicated person, you will see things in complicated ways.

To illustrate his point, he told me a story about how Prince Charles had been invited to tea, and when it was served, the tea bag was placed next to his cup, which contained hot water. Prince Charles drank the cup of hot water. The reason? He had been accustomed to people making tea for him. He simply did not know that the tea bag should be placed in the cup of hot water.

After Dr. Randas and I had finished coffee and he'd had a cigar, I gave him the album of photos I'd made. It was wrapped in green and gold paper, and accompanied by a card. He seemed to like the book, though he wasn't very effusive in his comments. "Nice book," he said. As he began to look through the book, he noticed a photograph I took of the patient in the Seattle a few days before the operation. He told me to look at the patients feet, swollen from the edema that results from poor circulation. As he turned from one page to the next, he scarcely took time to read the text. I had to point out parts of the text that I thought he'd like. These passages had taken me several hours to translate from English to Portuguese, and I'd even enlisted the help of a Brazilian friend, Wanderlan Silva, who lived in New York who offered suggestions via email.

For me, the book was about more than photos of heart surgery. It was the first project that I had ever worked on that combined all of the forces that I possess. I was able to connect with Dr. Batista after seeing him on television in a NOVA special. This took more than two years of postioning, calling heart surgeons across the U.S., meeting them and photographing them first so that I would be prepared to photograph Dr. Batista if the opportunity arose.

As soon as I learned I'd have the chance not only to meet him, but to photograph him in action, my mind spun into overdrive. I decided that I needed to meet the patient, interview him about his heart failure and its effects on his life, and photograph him before Batista arrived in Seattle from Brazil. A day later I was in the patient's home spending an afternoon learning about everything in his life that led up to his present heart problem. I made photos which I believe captured that moment in his life.

The morning of the surgery I had arrived at the hospital at 6:30 am. I introduced myself to Dr. Batista in Portuguese and within the hour I was helping him prepare a presentation to the hospital staff. An hour later I was at work documenting the first Batista Procedure in Seattle.

All of my passions in life came together in that book. My interest in people, in journalism, the art of the interview, the field of biology, the human heart, and of course, my love of Brazil.

I feel as though that book is pregnant, full of hope, snapshots of a life saved, captured in color and black and white, in English and Portuguese. When he made it from cover to cover in about 4 minutes, I felt like he probably hadn't absorbed it all. He did say that the photos were beautiful, and that the book was really cool. It was just a sense that I had that perhaps he's more into the process of the surgery than a document about it.

However disheartened I may have felt as a result of his perusal of the book, I noticed something later that made me feel better. It was much later in the same day, I was on one sofa, across from Dr. Randas, who was working on him laptop computer. His wife was sitting in a chair across the room by herself, looking at the photos in the book. She was letting it all sink in. In her silence, she marvelled. My memory of her at that moment made it worth it. I saw one of his sons leafing through the pages later on and he seemed to be interested, so I could tell it was being noticed.

It started raining relentlessly. After Dr. Batista had flipped through the book, we decided to go into Curitiba. As we drove into town, you could see the shopkeepers at the bakery, the paper store, and the drug store sweeping the rain off the sidewalk in front of their stores. We were on our way to get instant color photos. He's leaving tomorrow for India, where he will teach "The Batista Procedure" to surgeons in that country. He needs the pictures for a visa. I would travel with him, but then I'd have to change the title of this web page to "Jeffrey Luke's India Diary" and it would be too much work. So I think I'll just stay in Brazil.

I thought it would be cool to travel to India with him. I told him, "Você tem muita sorte que pode ir para India". That means, "You're really lucky to be going to India". He looked at me as if I were crazy. He does not like that country much. It's overcrowded and dirty. Nonetheless, he'll be flying to Belo Horizonte, Brazil, for a surgery, then to Rio, and from there he flies to New Delhi, India via Frankfurt. I have no idea what I'll do during that time, so if the Brazil Diary is not updated for a while, it's because I'm looking for another computer.

I have been extremely lucky to have a good internet connection and the ability to upload my web site via the file transfer protocol (FTP) program that I brought with me to Brazil. Updating this web page is not a simple procedure. I am lucky to have been able to write to you thus far from Brazil. I can make no promises for the future.

I do think India would be a worthwhile trip, but the plane ticket is about $2,000, and that's just too much money for a one-week trip. I've just arrived in Brazil. There will many adventures here, for sure.

I realized that Dr. Randas and I have a skill in common. When we drive and have to do something with our hands, we steer with one knee. I have been doing this for years. This ability has been useful since my days as a newspaper photographer, when I used to have to load my camera while driving to an assignment. It's also a good way to steer when I need to floss late at night on the drive home. My dad is always very scared when I drive with my knees, but my uncle Skippy thinks it's cool.

While we were at photo place where they took the visa Polaroids, Dr. Randas received a call on his cellular phone. It was from the hospital, and they said they had a myocardial infarction (heart attack) on their hands. We got in the truck and started driving to the hospital.

Once we'd started driving, he realized that the truck was low on diesel. He was upset because he'd asked his sons to fill up a container with diesel at the farm, and leave it in the truck for when he's running low. Most gas stations in the city don't sell diesel. So there we were, trying to get to the hospital to do the surgery, and we're almost out of fuel. Fortunately we found a place, and then we were on our way to the hospital.

One of the things I've learned about Dr. Randas is that when it comes to work, he moves quickly. So when we arrive at the hospital, I have to change into my operating scrubs, mask, shoe covers and cap very quickly. Today I think it took about 45 seconds, an improvement over 2 or 3 minutes yesterday.

Today was emergency surgery. One of the patients' coronary arteries was blocked, and Dr. Randas had to cut a piece of saphenous vein from the patient's leg and suture it between the ventricular wall and the aorta so that the patient's heart would be able to receive freshly oxygenated blood. The fascinating aspect of today's operation for me lay in the fact that he did the whole procedure on the heart while it was still beating. In the United States, almost all surgeons stop the heart from beating and then circulate and oxygenate the blood with a heart/lung bypass machine. Dr. Randas performed the entire surgery "off-pump," or "sin bomba.".

We had to move very fast to get to the O.R. and begin work. One more suggestion for anyone interested in photographing heart surgery: Always keep your cameras loaded, one with color, the other with black and white, and have them out of the bag and ready to go. There was no time to wasted today with extra movements or looking for light meters, film, etc. No matter what country he is in, or what time of day it is, Dr. Randas similarly tries to be ready for whatever might come his way. "I keep my knife sharp," he once said wryly.

Dr.

Randas operated without fancy tools on a beating heart and finished the whole

operation in about 40 minutes. I've never seen such a quick and efficient

coronary bypass.

Jeffrey Luke's Brazil Diary

October

28, 1999

In transit between Curitiba, Brazil

and Foz do Iguacu

|

Jeffrey Luke's Brazilian Diary

October

29, 1999: 8pm

Foz do Iguacu, Brazil

I arrived in this small frontier town at 7 am after a torturous 10 hour bus ride. During this all-night crusade, I felt intense claustrophobia for the first time in my life. The ride was bumpy, it was hot, humid and dark inside, and the windows did not open. We stopped for rest only once. Writing about this experience would require that I relive it, so I'll move on.

This town is well known for "As Cataracas do Iguacu," some of the most famous waterfalls in the world. The falls form Brazil's border with Argentina and Paraguay, so I will probably visit one of those countries before long.

When I got off the bus I was very sleepy, having slept very little during the ride. The sun was excessively bright, and the first thing I wanted to do was find a place to sleep all day long. But the brilliance of the sun and newness of the place would not let me rest. I searched for a place to put my clothing and camera gear.

I checked out the hotel rates. They ranged from R$105 (that's in the Brazilian currency, the Real) to about R$60. I went to one hotel, and they quoted me R$40, then as I walked down the street a bellboy chased after me and said it was actually R$35. That kind of thing doesn't happen in the U.S. I found a youth hostel, and with a price of R$10 a night, I though I'd stay there. The rate of exchange is 2 Reis (plural of Real) for a dollar, so that's only US$5 a night. And the most expensive hotel I found was about US$52 a night, which isn't that outrageous for an American in the United States, or a tourist here, I suppose. But I'm living in Brazil, and as long as I'm here, I have to think like a Brazilian. That means being practical. And they way I figure it, I can make my money last 10 times as long by staying in a hostel which costs a tenth the price of a hotel, I'll do it. You wake up to the same sun in the morning.

I checked into the youth hostel. The hostel experience is a strange one. You never know who you'll room with. I was told I would be sharing a room with some Australian guy, and was introduced to him briefly in the lobby. The whole idea of trusting your life to someone you don't know, the fact that you will go to sleep at night and hope that they won't go psycho on you and end your life in your sleep is an odd thought to ponder, and I'll choose not to as that is where I'll sleep tonight. My personal philosophy on sleeping in a room with a stranger is that it's a good idea is to keep anything of value in a bag, but don't put it under your pillow or bed. Make it easy for him to get to. Because if he really does want my stuff, I'd rather he could get it quickly in the middle of the night while I sleep rather than have to wake up to his violence and frustration at not being able to find my money/watch/camera. Would you let a total stranger sleep in a locked room at your house or in your apartment? That's what you get at a hostel. All he needs is a face and not enough $ for a hotel, and you can call him "roommate."

Then I found a great spot, Cafe Trigo, to eat a breakfast of fresh bread with butter, and coffee. I walked around. I found the place that I'm writing this diary entry from. It's called "Cafe Pizza Internet." It has neither a cafe, or pizza, but it does have internet access.

After my walk I found a gym for my workout. I haven't had good exercise since I left the U.S., it's been all surgery and horseback riding. So I went and asked if I could workout on a day pass, and the woman at the desk said that I could pay for a weightlifting class, but they don't have a day pass. So I asked if I could pay for the class, and just work out on my own. "Of course," she said. It cost R$3, which is a $1.50 in the U.S.

The equipment was really bottom of the line. Flimsy, it looked like home exercise junk. The treadmills were constructed in a skimpy way, barely long enough or wide enough to keep from falling off. I got on one of them to get a brisk walk going, and this fitness instructor guy comes up to me and asks me where my sneakers are. I was wearing the same boots which have served me well in horseback riding on the Brazilian outback, heart surgery, and now a gym on the frontier. I told him these were all I had, and he asked me how long I planned to be on the treadmill. I picked a low number. "Four minutes," I told him, thinking that he would let me use them for that short interval (the boots have rubber soles, I was walking, there was really no damage at all being done.). He did some mental gymnastics, looked at me, and told me that was not enough time. "Ten minutes you will need," he said.

After my legs were warmed up, I went over to their leg press machine, a standard apparatus which you load with weight plates, sit down in, and shove with your legs to work your quads and hamstrings. I started to load weights onto it, and realized they didn't have enough weight in the room for my workout. I usually start at about 630 pounds and work my way to about 810, which I'll squeeze out about 10 reps with. They didn't have enough for that. They had about 450 pounds in the gym, and while I was loading all of their weights onto the machine, I was getting really strange looks from the 5 or 6 guys who were working out. It was apparent that as big as they were, and some were really muscled, no one had attempted this heavy a weight. I did about 10 reps and then 15 and 20 and it was pretty boring. I stopped and went over and did some other exercises and eventually settled on doing the standing military press, which exercises the upper body. I needed much less weight for that exercise, and it went well.

I know that the those are really heavy weights. Those who read this diary and don't know me might imagine that I'm some hugh musclebound man who primps and postures before a mirror. I assure you, I'm not.

I began working with weights regularly last year. I would never have thought of going to a gym when my friend Louis came to visit me in Seattle. He is a photographer and had just come to town for a photo shoot. After he was finished with his assignment, he came by my place and mentioned that he was on his way to workout, and when he was finished, he'd stop by and we could get some dinner together.

I don't remember if I was curious or just didn't feel like hanging out in my apartment any longer that day, but I went with Louis to the gym. He showed me how to perform some basic lifts: The upright row, squats, lat pulldowns, curls, shoulder press and a hamstring exercise. I had fun trying the exercises. When I told him I might trying going to the gym on my own sometime, he told me how long to work out, and how frequently to go to the gym. It's important to work out no more frequently than every four days to provide my body with time to recover from these workouts. They last only one hour, but they are the most intense hour of work that I might ever experience.

I enjoy a good workout. Not in the smiling, skipping, happy way, but in a satisfying way that arrives only through discipline. The endorphins flow, the body has gone all out. It has worked hard and knows that it deserves its rest after a goodworkout. It is time to eat a big meal and sleep deeply.

When I mention doing leg presses at 600 or 800 pounds, you must understand that I didn't start at those weights. I started at much lower weights with other leg exercises. When I was ready, I began leg pressing 300 pounds, then worked my way up incrementally.

Many people in gyms that I go to are surprised at the weights that I work out with. They cannot imagine attempting such lifts. Mentally, they don't think they can, and as I result they stay with lower weights, never trying to attain a higher level of physical performance.

One thing that working with weights has taught me is that what you train your body to do, it will respond to. It is more incredible than any machine made, because when you put it under tremendous stress, it gets stronger. When I realize how my body can adapt to the work I throw at it, I begin to see how the same kinds of challenges affect the mind. I try to push myself to try the things that scare me the most. I ask myself the hardest questions and see how my mind finds the answers on its own.

Many people would think that I'm crazy to go to a gymnasium on a hot day in Foz do Iguacu instead of going to the waterfalls or learning about Brazilian culture. But the sticking with the discipline is important. Because when the body is happy, the mind is too. With the strength I gain from working with very heavy weights, it is easier to carry a heavy camera case, climb a steep hill, ride a bike hard and fast, or hold on tight while riding atop a galloping mustang.

After my workout I returned to the youth hostel to take a shower. I was so glad to have brought my own shampoo from the states, and as I turned off the faucet, I realized the first drawback of hostel life. There was no towel. I wondered, what could I use to replace a towel, and my mind flashed on this green bandana I had packed. Well, it's not a very good substitute, but then I found a clean cotton shirt in my bag which did the trick. So, as president Roosevelt said, "You make due where you are with what you have. Or, as they say in Brazil, "Quem nao tem cao caca com gato," which means, "He who doesn't have a dog hunts with a cat."

In the late afternoon, I went to the post office with a letter I'd written to a friend in the U.S. I arrived at 5:30, as I'd been told they were open until 6:30. Not so. They closed at 5. I was standing there outside the post office, sweating after the long walk, and a mailman walked by. I asked him if I had put enough postage on the letter to drop it in the box outside, and he said no. Then he told me to follow him and guided me into the post office through the back door. There were a few women closing their cash drawers, and they accepted my letter (it turns out that I had applied the correct postage), and when I asked if they would sell me some more stamps, they obliged. They were so kind about it, even though they were helping me after hours. I cannot imagine a U.S. postal employee letting me into the P.O. a half an hour after closing. Ever.

I had a great meal of rice, beans, farofa and spaghetti, washed down with a guarana soda to complete a great first day in Foz do Iguacu.

Jeffrey Luke's Brazilian Diary

October

30, 1999: 12:45 pm

Foz de Iguacu, Brazil

I spent most of this day thinking about what journalism is all about. I wonder if it can be purely objective. We are told to just give the facts. Yet every time I lift the camera to my eye, my photos are informed by my life experiences. That is why (thank goodness) no two photographers take the same pictures. The same goes for writers. A writer reflects, in each phrase, ideas which are linked to their interests, ideas and passions in life.

My entire journalistic training has stressed the importance of objectivity. We're taught to the the facts, the who, what, when, where, why and how. When you read about a news event, you don't want a reporter's interpretation of what happened, you just want the info. Yet I wonder how objective we can be. I don't know if I'd ever want to be objective. Fortunately, this Brazilian Diary is a different thing.

This is a chance to be part journalist, part essayist, a collector of pieces of other people's lives. I learn about their daily experiences, and the way these form their philosophies. I hunt and gather during the days, and at night I cook it up and serve it into these pages, making connections with my own life experiences.

Photography has always been a love of mine. It is a way of creating a diary of my life. I photograph everything that interests me. Some people collect coins, stamps or knick-knacks they find at flea markets. I collect experiences in my life with photos.

Writing this diary is very different from taking pictures. It is becoming such a powerful experience that I've begun to feel that the experience of writing has become more fascinating than photography. Sometimes writing is more exciting than the experiences themselves. I'm living each day just for the excuse to put the pieces together into a mosaic.

I make connections between stories that people share and my own history. One idea connects to the next, and I ask people questions about the things I don't understand. They provide the tiles and I bring the mortar. I can already start to begin to see a few disparate ideas coming together for my next entry in a chaotic, yet purposeful way. In my head it feels like a reverse of the big bang, all of the matter coming together and condensing into something tight, pure and dense.

Let me blend one of Dr. Batista's ideas with some observations of my own.

Dr. Batista says that nature is simple, we are the ones that complicate things. He has devised this remarkably simple operation that requires splitting apart the patient's breastbone, cutting into the heart, and removing a chunk of muscle to restore a grossly enlarged heart to a more normal size.

Yet I wonder how simple this is, and if this is what nature meant to happen.

Maybe people who are really sick are meant to die.

I once heard a surgeon say, "Bad things happen to sick people".

My own father had a heart attack seven years ago, and if it weren't for quadruple bypass surgery, he might not be around today. So I'm very thankful for the advances of medicine and science. Still, I keep wondering how many new discoveries we need to make to prolong life.

If a person in your family has ever had to have open heart surgery, you understand the agonizing unknowingness that fills the hours while they are under the knife. There are no promises that they will live, and often the surgery occurs so shortly after a heart attack that the time in between is condensed. The time you would like to make the big decision is not there, and it often feels like there is no decision to make. You either do the surgery or you'll die.

I got the phone call at 9:40 a.m. on Monday morning, June 5, 1992. I was at El Mundo, the Spanish language newspaper where I worked, and a Peruvian man named Marino who sold advertisements came to get me and told me that my father was on the phone, that he wanted to talk to me. My dad told me first that there was nothing to worry about. That's when you worry. He told me that he'd had a myocardial infarction. I think he used the clinical term because saying "heart attack" is admitting that something horrible just happened.

He had been at his health club doing the Stairmaster that morning, he said, and after his workout he felt a fluttering feeling in his chest, "The anticipation of a young child at his first circus," are the words he used. Instead of driving himself to work, he drove to his doctors office. Moments later he was being rushed to a major hospital in an ambulance.

I met went right over to the hospital. I didn't really know what was next, what it all meant. He had some tubes, monitoring equipment hooked up to him, but things didn't seem to chaotic. It seemed like he'd been stabilized and everything was under control. I was the only family member around. We lived in the Boston area, my sister was at college in Bronxville, New York and my dad's brother, uncle Skippy, was in San Diego, CA.

Things changed real fast. My dad, while he was having some additional tests performed, had another heart attack, right there at the hospital. They said he had to have bypass heart surgery. My sister flew in from New York and my uncle from California. Skippy had not yet arrived as my dad went under for surgery. No one had told me or my younger sister what the odds would be for his surviving this. We walked around Harvard Square for hours. We stopped to hear a street musician named Mary Lou Lord play guitar. She sang a song about Romeo and Juliet. We ate though we were not hungry. It was a holding pattern with great consequences. There is nothing we could do but wait.

The day passed very slowly. I think that after 3 or 4 hours we found out that the surgery was over and he had lived through it. After 6 hours we were able to go into the cardiac care unit and see him. Although they warned me that he would look differently after surgery, it would look as though he had been beaten up in a fight, I was not prepared. The sheer horror of seeing my dad with all of those things stuck into him, the puffed-up face and the bubbles of oxygen drifting up through the water of the oxygen delivery system were more than I could handle, and I fainted. I do remember a few nurses lifting me from the floor, breaking the ammonia capsule, and insisting that I keep my head down low.

I am extremely thankful for the advances in cardiac surgery that have allowed my father to survive to this day. Still, I keep wondering about the need to prolong life through surgeries, drug therapies and radiation treatments.

Today I've been thinking that eventually we will all die of something. You may have a heart problem cured, but then get hit with cancer. Maybe chemotherapy works and the cancer is halted, but you start to lose your mind to Alzheimers. I think if I were sick, I'd definitely want any cure I could get my hands on, I'd want the benefit of any remedy under the sun. Yet right now I wonder how long one is really supposed to live, and more specifically, how do you decide that maybe it's time to die.

I have a friend who doesn't like the idea of heart surgery. But then, who does. He has two children, on in his 20's, one in her 30's. And he says, if he ever notices the signs of a heart attack coming on, he's just going to take two aspirin (which thin the blood) and hope it passes. If it doesn't that's that. Now to me, that seems like such a simplistic response to a heart attack in an age where surgery is so routine. However, I think my friend's idea is wise. If you can stop the heart attack simply with aspirin, give it a try. If it doesn't work, maybe it's time to die.

Now that seems

natural. And simple.

Day spent re-organizing and updating web page.

|  |